FoundationDB originally used an embedded SQLite B-Tree as its storage engine:

“The current FDB storage engine consists of an unversioned SQLite B-tree and in-memory multi-versioned redo log data. Only mutations leaving the MVCC window (i.e., committed data) are written to SQLite.” [1]

Later, the project transitioned to Redwood, a B+Tree built over an arena allocator with page-level MVCC (all observable via code and merged PRs). In contrast, Apache Cassandra is a pure LSM-Tree system consisting of a memtable, commit log, and SSTables [2].

What does this imply? Decoupling. FoundationDB exhibits one of the most elegant and sophisticated architectures among distributed systems, cleanly separating transactional processing (coordinators, proxies, resolvers) from data storage (Storage Servers). This separation enables non-trivial storage-engine flexibility conceptually switching between an LSM-Tree and a B+Tree backend.

Yes, really.

LSM-Tree vs. B+Tree

Comparing these structures could easily become a long theoretical discussion. Instead, we differentiate them using structural metrics and experimental metrics.

A classic structural framework is the “amplifications”:

- Write Amplification (WA) → WAL + flush + compaction; increases when many SSTables exist.

- Read Amplification (RA) → memtable + SSTables; multiple binary searches + merges.

- Space Amplification (SA) → tombstones + compaction buffers + fragmented pages.

For our storage engine, we will implement an LSM-Tree.

Write-Ahead Log (WAL)

As described in Cassandra’s documentation [2], its WAL (CommitLog) follows a long tradition of database logging rooted in IBM’s ARIES algorithm. FoundationDB also has a WAL, but with semantic differences: the Transaction Log (TLog) acts as the distributed, ordered, replicated WAL of the cluster.

The core idea behind a WAL is the write-ahead principle:

Before any change is applied to the physical data structure, it must first be recorded in an append-only, sequential, durable log.

This makes the WAL the first component we must implement: it defines the commit path.

In a local storage engine, the WAL is a sequential file used for crash recovery, durability, and state replay. In FoundationDB, WAL semantics exist at the distributed level: the TLog is replicated, ordered, asynchronous, multi-stream, and pipelined.

Memtable: Role and Structure (Red-Black Tree)

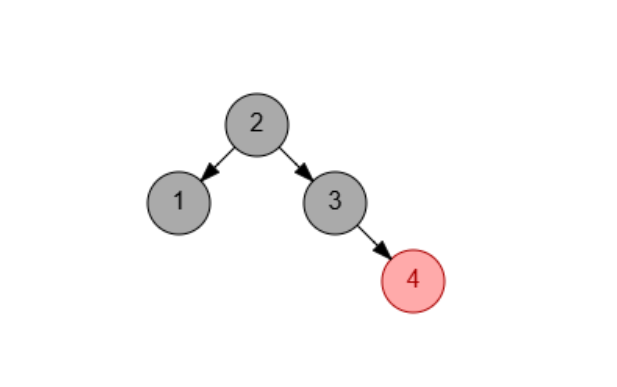

For this engine, we choose a classic LSM-Tree design. Although the original O’Neil paper [3] is dense, the ScyllaDB design notes [4] provide an approachable summary. An LSM-Tree maintains an in-memory sorted structure the memtable often implemented using a red-black tree for ordered key/value access.

This ensures that all entries are sorted lexicographically by std::string keys.

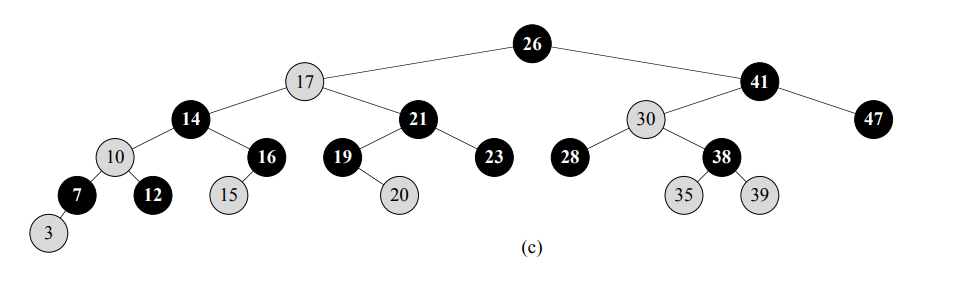

Red-Black Tree illustration (Cormen et al., Introduction to Algorithms, 3rd Edition).

We define our memtable type as:

typedef std::map<std::string, MemEntry> MemTable;

Where MemEntry is:

struct MemEntry {

bool is_tombstone;

std::string value;

MemEntry() : is_tombstone(true), value() {}

MemEntry(const std::string& v) : is_tombstone(false), value(v) {}

};

Thus, our MemTable is a red-black tree ordered by key, mapping std::string → MemEntry.

It will be central during WAL recovery.

To visualize what the memtable looks like after replaying the WAL, consider the following sequence of operations:

wal.appendPut("a.txt", "AAA");

wal.appendPut("c.txt", "CCC");

wal.appendDel("b.txt");

wal.appendPut("d.txt", "DDD");

WAL::MemTable mem;

size_t applied = wal.recover(mem);

std::cout << "Registros aplicados desde WAL: " << applied << std::endl;

for (const auto& kv : mem) {

const auto& k = kv.first;

const auto& v = kv.second;

std::cout << k << " -> "

<< (v.is_tombstone ? "DEL" : ("PUT(" + v.value + ")"))

<< std::endl;

}

After recovery, the memtable (which is implemented as a std::map<std::string, MemEntry>) contains the latest logical state for each key. Since std::map is a Red-Black Tree, the keys are stored in sorted order:

a.txt → 1

b.txt → 2

c.txt → 3

d.txt → 4

If we visualize the underlying Red-Black Tree structure, one valid representation of the memtable is:

c.txt (black)

/ \

b.txt (black) d.txt (red)

/

a.txt (black)

If we annotate each node with its logical value (PUT or DEL), the tree becomes:

[c.txt | PUT "CCC"]

/ \

[b.txt | DEL ⊘] [d.txt | PUT "DDD"]

/

[a.txt | PUT "AAA"]

A few important points:

- The memtable contains exactly one entry per key, representing the most recent PUT or DELETE.

- A DELETE does not remove the key from the memtable; instead, it is stored as a tombstone (is_tombstone = true). Tombstones are necessary so that future SSTable flushes or compactions can correctly shadow older data.

- The exact shape of the Red-Black Tree may vary (due to balancing rotations), but the sorted order of keys is always preserved, which is crucial for LSM-tree flushes and range scans.

Repository link KV-LSM-RP

WAL Implementation Detail: POSIX vs. <fstream>

Many tutorials use <fstream>, but database engines typically rely on low-level POSIX I/O (open, read, write, fsync, close) for explicit control over durability guarantees.

Opening the WAL file:

void WAL::openFile() {

fd_ = ::open(path_.c_str(), O_CREAT | O_RDWR | O_APPEND, 0644);

if (fd_ < 0) {

throw std::runtime_error("WAL: open failed");

}

}

FoundationDB: Flow I/O, Actors, and POSIX

FoundationDB uses Flow, its cooperative concurrency runtime.

The asynchronous file interface lives in:

foundationdb/flow/IAsyncFile.actor.cpp

A Flow test case (simplified):

TEST_CASE("/fileio/rename") {

state int64_t fileSize = 100e6;

state std::string filename = "/tmp/__JUNK__." + deterministicRandom()->randomUniqueID().toString();

state Reference<IAsyncFile> f = wait(IAsyncFileSystem::filesystem()->open(

filename,

IAsyncFile::OPEN_ATOMIC_WRITE_AND_CREATE | IAsyncFile::OPEN_CREATE | IAsyncFile::OPEN_READWRITE,

0644));

wait(f->sync());

wait(f->truncate(fileSize));

// ...

}

And the real implementation is exercised through:

foundationdb/fdbserver/BulkLoadUtil.actor.cpp

For example, asynchronous file reads:

ACTOR Future<Void> readBulkFileBytes(std::string path, int64_t maxLength, std::shared_ptr<std::string> output) {

state Reference<IAsyncFile> file = wait(IAsyncFileSystem::filesystem()->open(

abspath(path), IAsyncFile::OPEN_NO_AIO | IAsyncFile::OPEN_READONLY | IAsyncFile::OPEN_UNCACHED, 0644));

state int64_t fileSize = wait(file->size());

output->reserve(fileSize);

// ...

}

In short:

- Flow provides the asynchronous interface and deterministic test harness.

- IAsyncFile / IAsyncFileSystem define the I/O API.

- Platform.actor.cpp implements POSIX calls (pwrite, pread, fsync).

- Higher layers (e.g., Redwood, BulkLoad, TLog) use these building blocks.

The pattern looks like:

Flow (tests, actor interfaces)

↓

IAsyncFile / IAsyncFileSystem (abstract API)

↓

Platform.actor.cpp (POSIX / Win32 backend)

↓

FDBServer / Redwood / BulkLoad / TLog (database logic)

References

[1] Zhou, J., et al. (2021). FoundationDB: A distributed unbundled transactional key value store. Proceedings of SIGMOD 2021. https://doi.org/10.1145/3448016.3457559

[2] Carpenter, J., & Hewitt, E. (2022). Cassandra: the Definitive Guide, (Revised) Third Edition: Distributed Data at Web Scale. O’Reilly Media.

[3] O’Neil, P., et al. (1996). The log-structured merge-tree (LSM-tree). Acta Informatica, 33(4), 351–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002360050048